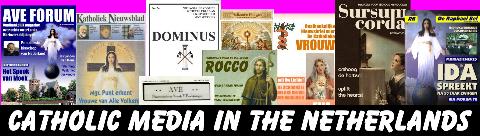

The best of Catholics on internet

See the Top5 of best viewed Catholic related websites at this moment. In Holland we don't have quality Catholic Newspapers like

l'Osservatore Romano or Avvenire in Italy. For years the main source for Roman Catholic News in the Netherlands was the "Katholiek Nieuwsblad", a weekly periodical.

But ezines on the internet are boosting and blooming. Very popular at this moment is the

AVE FORUM We monitor the main Dutch Catholic Media. On National level the "Katholieke Radio Omroep

KRO" dominated TV for decades in the Lowlands. But now local broadvasters like the Amsterdam based

MOKUM TV seems to cover the Catholics in a much appreciated new way.

We here translate the more interesting Dutch Catholic stories in English. Just click on the names of the magazines

on the black navigationbar, ans you see what's going on in the Netherlands.

Holy History

In 1930 there were more than 30 Catholic newspapers in the Netherlands.Now there is only the Katholiek Nieuwsblad. But

the ezines are gaining ground. Sometimes even unusual combinations can be seen, as is the case on the site of

Türkevi Amsterdam, a moslim migrant organisation that produced a

DVD about the Holy Virgin Mary, including her role in the Quran, Her House in Epheses in Turkey and Her apparitions in Amsterdam. As the popularity

of the Amsterdam apparitions (Mother of All Nations) is growing, so are the ezines about her.

In 1968 the organisation of Catholic Journalists (KNKJ) merged with the National Union of Journalists (NVJ) and in 1973

the Catholic Press Agency became part of the Religious department of the General Press Agency (ANP). In the next decades the

attention for religion in the printed media is declining.

But at the same time religion and spirituality never disappeared

from television and radio. The broadcasting associations raised in the 1920’s within the different religious and social-political

pillars until now still exist. Religious organisations have since 1957 direct access to the public service broadcasting system

by means of their own airtime, also financed out of the media-budget. These broadcasters are to some extent protected by law

and publicly financed. The press on the other hand, functions within a commercial setting and has no substantial and structural

state support by law or finances. They function in a fundamentally different situation than the (public) broadcasting system.

The radio- and television programmes on the Dutch national channels are produced by some 20 organisations. There are

Corporations established by law (NOS and NPS), Broadcasting associations (AVRO, KRO, NCRV, EO, BNN, TROS, VARA, VPRO), Religious

and other spiritual organisations (RKK, IKON/ZVK, HUMAN, OHM, NMO, NIK,BOS) and Educational broadcasters (TELEAC/NOT and RVU).

Political parties with one or more seats in the House of Representatives or in the Senate also have national broadcasting

time and advertising is centrally provided by the Radio and Television Advertising Foundation (STER). Every broadcasting organisation

(including the STER) is responsible for their own broadcasting time and the content of it. The NOS is the co-ordinating organisation

responsible for the management of the three television-channels and five radio-channelsand the co-operation of the different

broadcasting organisations within the system.

Three of the mentioned associations (KRO, NCRV and EO) have a religious background. The Catholic radio and television

organisation (KRO, 1925) and the Protestant radio and televisionorganisation (NCRV, 1924) both state in their mission that

they are inspired by the respectivelyCatholic and Protestant tradition. The Evangelical Organisation (EO, 1970) puts it stronger,

statingthey want to reach people with the Gospel of Jesus Christ using radio, television, internet and print. Religious organisations

do not manage these broadcasting organisations, they are in fact initiatives of religious citizens. The organisations have,

however, strong connections with religious organisations f.e. by means of religious advisers in their board.

The amount

of airtime granted, depends upon the amount of members these associations have, with aminimum of 300.000. All eight associations

have more than 300.000 members and, accordingly, haveeach at their disposal at least 650 hours of television broadcasting

time and 3000 hours of radiobroadcasting time. The NPS (cultural programming) has the same amount of hours and the NOS (news

and sport) has 1,300 hours of television and 1,500 hours of radio broadcasting time. In 2000, 300 hours of religious programmes

are broadcast on television, 2% of the total broadcastingtime by all broadcasting organisations. In the same year, 106 hours

of sacred music is broadcast, 1% of total broadcasting time and 16% of total music broadcasting (NOS, 2001). There are no

quota’s in the Media Act concerning the amount of religious programming except for section 50.6 and 50.7 stating that

the religious organisations and spiritual organisations shall use all their broadcasting time for areligious resp. spiritual

programme. These statistics however give limited insight in the type of programming and the total attention for religion on

television and radio.

The case of broadcasters ’Next to the above mentioned associations, religious organisations itself have since 1957

direct accessto the Dutch broadcasting system. This can be seen as an acknowledgement of the position of the church and religion

in society. According to section 39f of the Media Act the Media Authority mayallocate national broadcasting time to religious

and other spiritual organisations once every five years. In recent years, the amount of religious organisations getting access

to the public service broadcastingsystem has increased. This is striking comparing to the situation in the press where the

religious press has diminished strongly the last decades. The Media Authority grants broadcasting time to the organisations

who represent the main religious groups in Dutch society (Catholic, Protestant, Muslim,Jewish, Hindu, Humanist, Buddhism).

Just one organisation can apply on behalf of a religious groupin order to prevent fragmentation. Currently there are seven

religious and spiritual organisations with broadcasting time within the public service broadcasting system. IKON and RKK are

theoldest organisations, both started in the 1950’s followed by the Humanistic Organisation (1973), the Hindu Broadcasting

Network (OHM), Muslim Broadcasting Organisation (NMO) (both in 1993), Zendtijd voor Kerken (1994, part of IKON) and Buddhist

Union Netherlands (2000). The amount of airtime depends upon the amount of members of the religious organisation. The Christian

organisations (RKK, IKON/ZVK, NIK) still account for the majority of the granted broadcasting time.There was however a discussion

in 1999 and 2000 about the mutual dividing of broadcasting time amongst religious organisations for the period 2000-2005.

In particularly the NMO wanted more time because of the strong increase of Muslims in the Netherlands and of the attention

for the Islam in the western world. The time granted in the period 1995-2000 to the NMO has been doubled for television.

The Roman Catholic Church has direct access to broadcasting time with the RKK programmes and chose the professional media

organisation KRO to produce the programmes within a certain general formulated programme policy. This leads to a situation

where the editorial responsibility lies within the editorial boards of the different programmes and the management of the

KRO. The Church community, by means of the Episcopat and the mediabishop is responsible for the strategic decisions concerning

the broadcasting time (type of programming, formulation of focus groups etc). Central point of discussion in the evaluation

process of the RKK/KRO agreement was the tension between the regularity of the media and journalistic values on the one hand

and the wish of the Episcopate to be present in the media in a certain manner. RKK and KRO have no specific internal regulation

or policy concerning the broadcasting of religious affairs and debates, ensuring equal treatment of political viewpoints and

other religions andconsultation of religious groups. Editors of RKK and KRO work according to general journalisticvalues,

on the basis of the RKK/KRO agreement, KRO mission statement, a frequently updated policydocument and internal discussions

about journalism and religion. Religious advertising is no issue forthe RKK and KRO since the STER is responsible for all

advertising on national public radio and television.The protestant IKON (Foundation for inter-church broadcasting) is the

ecumenical broadcastingorganisation for the Netherlands. IKON defines religious programmes as programmes made on behalf of

nine protestant churches and based on their ecumenical roots.

The (religious) broadcasting associations have no direct, formal bonds with religious organisations and have by law a

more general task (see section 14 Media Act), this tension is less present, but not absent. Every broadcasting association

focuses more or less on a public within certain religious or social groups or with a certain mutual interest. The different

associations try to take different positions as a broadcaster and focus on different themes and approaches in making their

programmes. Dating from the past there are contacts between the boards of associations and certain political parties (VARA

and PvdA, AVRO and VVD, KRO/NCRV and CDA, EO and SGP/Christenunie).

On the local channels are more Religious and spiritual organisations. So has the Amsterdam Local Network (

Salto) several religeous programms. As is the case of Amsterdam local broadcaster

MokumTV, sometimes both Catholic and Muslims can join in one single programm.